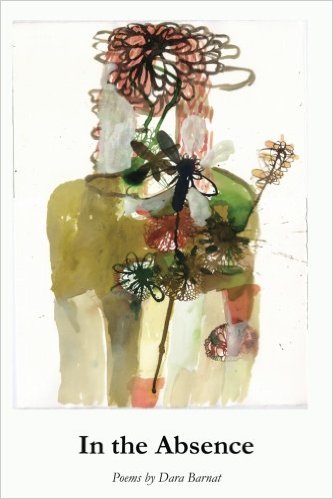

From IN THE ABSENCE

By Dara Barnat:

IMPRINT

I hear you’re gone and I fall with you.

In that place part of me stays,

like a hand in clay,

even as I make rice for dinner, boil water,

measure the grains,

pour wine, set out flowers with all their petals.

The imprint holds the loss of everything.

It holds what we thought was joy.

IN THE ABSENCE

Dark is just dark–

rooms and all we’ve built are nothing.

Chairs with their backs, tables with their legs, beds with their heads.

Outside, trees with their leaves.

I can’t write that wood into a vessel

that will carry us to a place

where life is a river never not flowing.

I close my hand around a filament of sun as it filters

through the window, try to catch

its meaning,

but light is just light.

PRAYER I DO NOT KNOW

There’s no one here, but me

alone. I close

my eyes and try

to remember your face,

its light, your

fingers, their light

touch, your laugh,

the lightness. I say a prayer

that is my own:

May we live

a thousand years together,

in another life.

Today’s poems are from In the Absence (Turning Point Books, 2016), copyright © 2016 by Dara Barnat, and appear here today with permission from the poet.

In the Absence: Dara Barnat’s In the Absence evokes a yearning of the spirit so strong that it becomes presence, its light unstopped.

Dara Barnat is the author of the poetry collection In the Absence (Turning Point, 2016), as well as Headwind Migration, a chapbook (Pudding House, 2009). She also writes critical essays on poetry and translates poetry from Hebrew. Her research explores Walt Whitman’s influence on Jewish American poetry. Dara holds a Ph.D. from The School of Cultural Studies at Tel Aviv University. She currently teaches at Tel Aviv University and Queens College, CUNY.

Editor’s Note: Dara Barnat’s first full-length collection begins by declaring that “Dark is just dark.” But the assertion casts a shadow question: Is dark just dark? For it is light that is at the heart of this work: “I close my hand around a filament of sun as it filters / through the window, try to catch / its meaning, / but light is just light.”

But “light is just light” is no more the truth of these poems — and the poet’s journey that unfolds across them — than “dark is just dark.” This work is neither a book of questions nor of answers. Instead, In the Absence is an honest experience of grief that explores the inevitable, never-ending pilgrimage inherent within loss: “I hear you’re gone and I fall with you. / In that place part of me stays, / like a hand in clay.”

Not since Li-Young Lee’s Rose have I been so slain by a book of mourning. Like Rose, In the Absence mourns the loss of a father while acknowledging that such a loss is anything but simple, that the complications of life remain a reckoning for the living. “The imprint holds the loss of everything. / It holds what we thought was joy.”

Held close within this incredibly moving and painstakingly wrought collection is a poem titled “Walt Whitman.” I had the honor of featuring this poem here on the Saturday Poetry Series in 2013 as I marked my father’s first yahrzeit (Jewish death anniversary). Tomorrow will be five years since my father’s death. What at one year could be commemorated with a single poem, five years later needs an entire book. Such is the nature of grief — it does not diminish; it grows. And in its growing it becomes more painful and more beautiful all at once.

In the Absence transforms the poet’s personal grief into communion. I will re-read this book tomorrow as I remember my father on his five-year yahrzeit, and I will grieve. But, more than that, I will say a prayer that is the poet’s and is my own: “May we live / a thousand years together, / in another life.”

Want more from Dara Barnat?

Buy In the Absence from IndieBound

Buy In the Absence on Amazon

Poems in YEW

Poems in diode

Interview in Poet Lore

Dara Barnat’s Official Website