From MY FRIEND KEN HARVEY

By Barrett Warner:

MY FRIEND DAVID BOMBA

MY FRIEND KEITH MARTIN

My friend Keith Martin is dead. He died in early April.

It’s kind of a busy month to die. The ground is softening—

rows raked and sown—jealous hues emerging like rye.

It’s weird that he died the same month I was born.

Now the ghost would be forever Aries, the passionate one,

the one who gets things almost right, who gets in his own way.

A friend is a brick against the sweet hereafter. Lose a friend

and you lose a brick. Lose Keith and you lose a wall.

It’s just a matter of time until the roof falls down.

Marsha his wife sat cold on offers coming quickly on his land.

I don’t blame her holding out for more, but suffered lifetimes

are always cheap. I gave away anything I ever tried to sell.

No one ever wants to buy what you don’t love.

Their house is a quarter mile away, through dense spite trees

planted by our neighbor so he wouldn’t have to look at Keith getting out of his car.

I can’t imagine hating someone so much I’d plant trees.

One dog’s not enough, and two dogs are too many.

That’s how Keith would talk, like Ben Franklin.

He wanted me to feel better, but I never did.

MY FRIEND LARRY MCKEE

My friend Larry McKee notices each leaf in an oak forest.

I see firewood, fence boards, squirrels, squirrel stew.

I hustle through life’s minor beauty to make myself sweat,

wearing work on my face like khol.

I am trying to say I don’t belong here, don’t deserve

this world. I need to earn every second of it.

If I stop sweating I’ll stop earning.

It’s why I’ll always have a job, and Larry, a passion.

Someone ate this, he says.

He holds a 175-year-old raccoon femur.

Someone knelt here in 1841 and prayed for something.

Maybe, yes, there was singing. Listen! Sobs and singing.

I have been sweating all day and all night and all year.

It’s only a matter of time before I exile myself.

It would be nice if Larry could learn from me too

but I have nothing to teach, even about drinking.

Larry grows the mint, makes ice from spring water

collected in caves, smokes the bourbon over apple wood.

He has a special black basalt rock that fits his hand

to crush the beautiful ice into manageable debris.

He takes so long to make a two minute drink

that I’m drunk on beer and hung over before his first sip.

Still, it’s the best I ever tasted.

And of course, the next day, I steal the rock.

The things I’ve bashed. The cars. The lives. The dogs.

The sweat that flew off my brow. The wasted muscle.

One night I pound some lamb into burgers, smother it

with sheep cheese, and I think, Larry would have admired this.

I call him up to brag about the recipe. His wife Hannah

passes over the phone. Sounds delicious, he says.

We haven’t spoken in thirty years. Leftover enchiladas for us,

Always better the second night, filled with grilled chicken cut up

Small mixed with salsa and corn cut off the cob. On the patio,

Watching fireflies and hummingbirds until dark.

Couple extra chairs at the table if you’re ever in the neighborhood.

The things I learned from Larry. The things I never learned.

Today’s poems are from My Friend Ken Harvey, published by PubGen, copyright © 2014 by Barrett Warner, and appear here today with permission from the poet.

My Friend Ken Harvey: “Nostalgia and sentiment were dirty words in poetry until Barrett Warner’s My Friend Ken Harvey came on the scene. Here we have a chapbook that shows us the many forms of love, how relationships can be measured as ‘not enough war or too much war in someone’s life,’ and how the simplest moments can be transcendent, all while dipping in and out of the sepia tint of memory.” —Dakota Garilli, Book Review: MY FRIEND KEN HARVEY by Barrett Warner

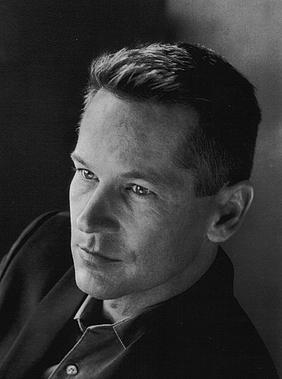

Barrett Warner’s poems, stories, and essays have appeared in newsprint, paper and online since 1982, and most recently in Entropy, Revolution John, and Four Chambers. In 2014 he won the Salamander fiction prize and the Cloudbank poetry prize. He has a website where he blogs about bathing, medication, gardening, Proust, and Kalamazoo.

Editor’s Note: Struck by the unique nature of this collection, I asked the author if he would share a few words on his vision and process. “To me,” he replied, “the biographical poem is an ekphrastic poem, but instead of writing about a Hopper painting or a Grecian urn, I’m writing about everyday people with whom I’ve had some moment of fantastic empathy.” What is “fantastic empathy,” and how does it translate from lived experience to poem to reader, I wonder. I find my answer in my own experience in reading these poems. “I’ll have the starfish, Bomba says,” because “Everyone should be allowed to order what they want / even if it’s not on the menu.”

This collection is at times hilarious, at times touching, at times lyric, simple, and stunning. “A friend is a brick against the sweet hereafter. Lose a friend / and you lose a brick. Lose Keith and you lose a wall,” Warner writes of the death of his friend Keith Martin. “I am trying to say I don’t belong here, don’t deserve / this world. I need to earn every second of it,” he writes, from some honest place between existentialism and a search for meaning. In a way, these poems are–as the poet says–ekphrastic, biographical, minute in their reports of human interactions. Yet in another way they are meta, like staring up at the night sky and trying to truly grasp what you are seeing. From the minutiae to the horizon, I suggest reading and rereading these poems and seeing where the experience leads you.

Want to see more from Barrett Warner?

Entropy

Cultural Weekly

Lines + Stars

Quarter After Eight

drafthorse