From OLAM SHANA NEFESH

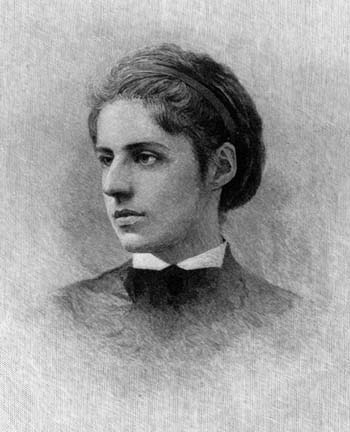

By Jane Medved:

SIRENS

They think it is the young girls singing

you see, we pull them to us as smoothly

as oiled rope uncurls into golden braids.

It only takes a few minutes before everything

they see is woman. The pale skin of the sails

spreading like thighs, the thick knots

that tie the anchor turning to strands

of dampened hair held by a lover

before she shakes it free. The salt tastes

as sweet as sweat and soon the ship’s thrust

into the sea becomes unbearable.

This would be enough for galley slaves,

soldiers who tattoo fortunes on their scars,

the simple, parched sailors. But they are not

the ones we want. When we see the heroes

whose fierce deeds fall like hammers, we lay

aside our nocturne of desire. We sing instead

as a mother holds a dying child until

the horizon is the circle of our arms, the wind

a cloth wrapping them in its whisper, the waves

a gentle hush upon each creaking of the deck.

“Do not be afraid. You will be remembered and reborn.”

WHITE FIRE

There is a cable and it reaches

from the side of loving kindness

to the cold window across the room

taking over the function of your heart

which is tired of trying to make blood

out of air. Some days it’s just too hard

to keep on lifting, to appear in a robe

which keeps on falling, exposing

all sorts of intimate matters and the

little whispers beneath. Do not worry.

You are the hand, the page, the white fire

and you cannot be erased. The black letters

will burn and sing and declare themselves

but they are nothing without your silence;

which is not the absence of words, empty

as the howl of a bowl, but the promise made

between all words before they are spoken,

that they will reach across the black lines

and know each other again, even

if they no longer recognize themselves.

LEAVING A NOTE AT THE WESTERN WALL

There is a splintered door leading

nowhere and a lot of women crying

today I can’t even get near the wall.

Luckily I have my own tricks.

I place my arm over a young girl’s shoulder,

sigh sympathetically as she bends

her head in prayer, then edge myself

into her space. Everyone wants to touch

God’s face, to press their forehead

against his slippery cheek and brush

the pitted marks beneath, thank you

for my eyes, my legs, my arms, my breath.

Herod did a good job, the ancient stones

hold solid. They outweigh the base

of the great pyramids and nothing moves

them, perhaps they are even held up

by pleading, since every crack is filled

with scraps of blue-lined paper, torn

index cards, a piece of yellow legal pad,

a folded napkin, sealed envelopes, airmail,

express, please, listen, thank you for my eyes,

my legs, my arms, my breath, excuse me,

a woman pushes past me, excuse me please,

when she reaches for the wall a handful

of notes loosen and fall at our feet.

The chair behind me is piled with prayers

as morning, evening and darkness

make their requests, songs from the sons

of Korach even though their father moans

in the earth thank you for my arms,

my legs, my eyes, my breath, women beg

the matriarchs and children press letters

into fists of stone while God sends back his answers

– No and no and no.

Today’s poems are from Olam, Shana, Nefesh (Finishing Line Press, 2014), copyright © 2014 by Jane Medved, and appear here today with permission from the poet.

Olam, Shana, Nefesh: “‘Olam, Shana, Nefesh’ is a Kabbalistic phrase used to describe the three dimensions of Place, Time and Person. Olam is most commonly translated as ‘world.’ But in Hebrew olam comes from the root of the word ‘hidden.’ This implies that place always has an unrevealed element to it; that we are surrounded by a reality beyond what is immediately visible. Shana literally means ‘year.’ It invokes an image of repetition, re-visiting, return, a never -ending cycle of months. In the Jewish calendar time is not a passive backdrop to human endeavor, but an active force whose windows of opportunity open and close, blossom and die just like the seasons. Nefesh can be translated as ‘person’ but it refers to the spirit as well as the body; the infusion of the divine into the physical. This is an inherently volatile combination, since a human being always contains a push and pull between the material and the spiritual, the body with its appetites and fears and the spirit. This is ‘person’ as the container of the animal and the divine.” – From Olam, Shana, Nefesh (Finishing Line Press, 2014)

Jane Medved is the poetry editor of the Ilanot Review, the on-line literary magazine of Bar Ilan University, Tel Aviv. Her chapbook, Olam, Shana, Nefesh, was released by Finishing Line Press in 2014. Her recent essays and poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Lilith Magazine, Mudlark, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, Cimarron Review, Spoon River Poetry Review, Tupelo Quarterly and New American Writing. A native of Chicago, Illinois, she has lived for the last 25 years in Jerusalem, Israel.

Editor’s Note: Olam, Shana, Nefesh is an absolutely stunning collection. A rare assortment of meditations on myth and history, religion, spirituality, sensuality, gender and place. The questions posed are epic, the answers as small and as critical as breath. The poems themselves are absolutely gorgeous in their own right; lyric delights that any reader would feel indulgent slipping into, with moments like “The salt tastes / as sweet as sweat and soon the ship’s thrust // into the sea becomes unbearable,” “The black letters // will burn and sing and declare themselves / but they are nothing without your silence,” and “Everyone wants to touch / God’s face.” But this book is even more rewarding for those readers familiar with the rich landscapes the poems call and respond to. How rewarding is “Sirens” for those well-versed in Greek mythology, how brilliant “White Fire” for those who know and love midrash, and how masterful “Leaving a Note at the Western Wall” for students of religion and history, for Jewish women, for those who have been to Jerusalem’s Wailing Wall, who have “press[ed] their forehead[s]/ against [God’s] slippery cheek and brush[ed] / the pitted marks beneath, [saying] thank you / for my eyes, my legs, my arms, my breath.”

Want to see more from Jane Medved?

Tinderbox Poetry Journal

Lilith Magazine

Buy Olam, Shana, Nefesh from Amazon