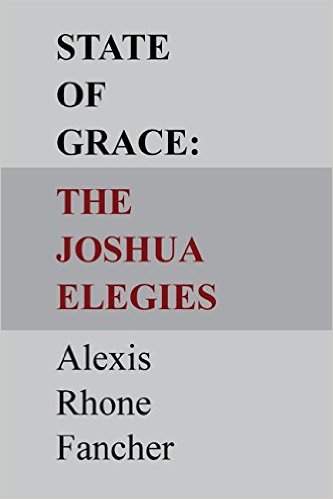

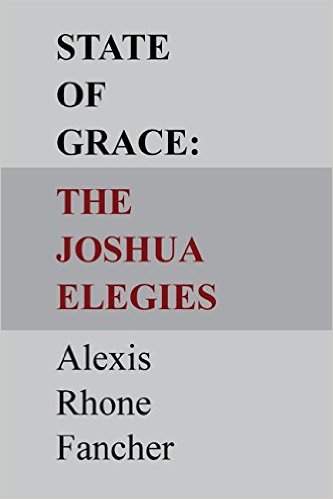

From STATE OF GRACE: THE JOSHUA ELEGIES

By Alexis Rhone Fancher:

DYING YOUNG

Midnight, and again I’m chasing

sleep: its fresh-linen smell and

deep sinking, but when I close my eyes I see

my son, closing his eyes. I’m afraid of that dream,

the tape-looped demise as cancer claims him.

My artist friend cancels her L.A. trip. Unplugs the

internet. Reverts to source. If cancer

will not let go its grip, then she will

return its embrace. Squeeze the life out of

her life. Ride it for all it’s worth.

By the time his friends arrive at the cabin

my son is exhausted, stays behind while

the others set out on a hike. He picks up the phone.

“Mom, it’s so quiet here. The air has never

been breathed before. It’s snowing.”

I put on Mozart. A warm robe. Make a pot

of camomile tea. The view from my 8th floor

window, spectacular, the sliver moon, the stark,

neon-smeared buildings, their windows dark.

Sometimes I think I am the only one not sleeping.

My artist friend wants to draw the rain. She

wants to paint her memories, wrap the canvas

around her like a burial shroud.

Tonight, a girl in a yellow dress stands below

my window, top lit by a street lamp, her long shadow

spilling into the street. She’s waiting for someone.

I want to tell my friend I’ll miss her.

I want to tell my son I understand.

I want to tell the girl he won’t be coming.

That it’s nothing personal. He died young.

SNOW GLOBE

Despair arrived, disguised as

nine pounds of ashes in a

velvet bag, worried so

often between my fingers

that wear-marks now stain

the fabric.

Is it wrong to sift

the remains of my dead son,

bring my ashen finger to my

forehead, make the mark of

the penitent above my eyes?

His eyes, the brown of mine,

the smooth of his skin, like mine.

Unless I look in the mirror

I can’t see him.

Better he’d arrived

as a snow globe, a small figure,

standing alone at the bottom of his

cut-short beauty.

Give him a shake, and watch

his life float by.

OVER IT

Now the splinter-sized dagger that jabs at my heart has

lodged itself in my aorta, I can’t worry it

anymore. I liked the pain, the

dig of remembering, the way, if I

moved the dagger just so, I could

see his face, jiggle the hilt and hear his voice

clearly, a kind of music played on my bones

and memory, complete with the hip-hop beat

of his defunct heart. Now what am I

supposed to do? I am dis-

inclined toward rehab. Prefer the steady

jab jab jab that reminds me I’m still

living. Two weeks after he died,

a friend asked if I was “over it.”

As if my son’s death was something to get

through, like the flu. Now it’s past

the five-year slot. Maybe I’m okay that he isn’t anymore,

maybe not. These days,

I am an open wound. Cry easily.

Need an arm to lean on. You know what I want?

I want to ask my friend how her only daughter

is doing. And for one moment, I want her to tell me she’s

dead so I can ask my friend if she’s over it yet.

I really want to know.

Today’s poems are from State of Grace: The Joshua Elegies (KYSO Flash, 2015), copyright © 2015 by Alexis Rhone Fancher, and appear here today with permission from the poet.

State of Grace: The Joshua Elegies: “Alexis Rhone Fancher’s book, State of Grace: The Joshua Elegies, maps in searing detail a landscape no parent ever wants to visit—a mother’s world after it’s flattened by her child’s death. Though her son’s early passing was ‘nothing personal,’ her poems howl with personal devastation. They insist that the reader take the seat next to hers in grief’s sitting room and ‘imagine him in his wooden forever.’ Fancher grapples with how to reconcile oneself to the slow loss of memory’s fade-out, and with how to go on living without betraying the dead, how to ‘[s]queeze the life out of / her life.’ You’ll need tissues when you read this book, but it’s well worth rubbing your heart raw against the beauty of these poems and their brave, fierce honesty.” — Francesca Bell, eight-time nominee for the Pushcart Prize in poetry, and winner of the 2014 Neil Postman Award for Metaphor from Rattle

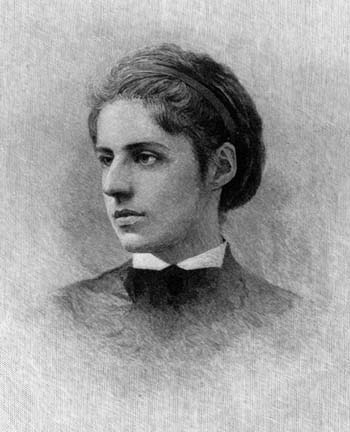

Alexis Rhone Fancher is the author of How I Lost My Virginity To Michael Cohen and Other Heart Stab Poems, (Sybaritic Press, 2014). Find her work in Rattle, Menacing Hedge, Slipstream, Fjords Review, H_NGM_N, great weather for media, River Styx,The Chiron Review, and elsewhere. Her poems have been published in over twenty American and international anthologies. Her photos have been published worldwide. Since 2013 Alexis has been nominated for three Pushcart Prizes and two Best of The Net awards. She is photography editor of Fine Linen, and poetry editor of Cultural Weekly, where she also publishes The Poet’s Eye, a monthly photo essay about her ongoing love affair with Los Angeles. www.alexisrhonefancher.com

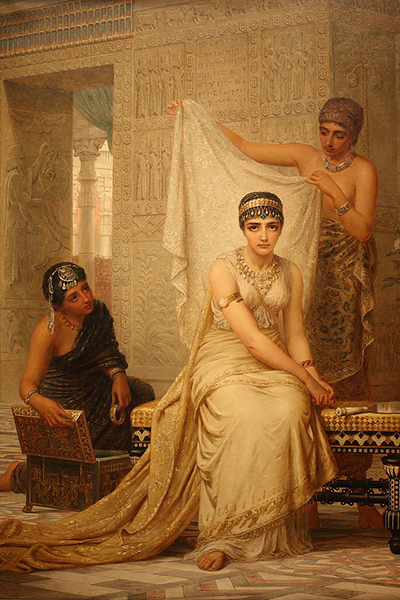

Editor’s Note: The poems in today’s collection slew me. Long after I finished reading them, they stayed with me, a specter. As I nursed my young son, worried over his maladies, rejoiced in his small accomplishments, there in the shadows was the poetry of Alexis Rhone Fancher reminding me that life is precious, fleeting, that nothing should be taken for granted, that anything–no matter how dear–can be taken away.

It is impossible not to be moved by these poems. By “a girl in a yellow dress [who] stands below / my window, top lit by a street lamp, her long shadow / spilling into the street… waiting for someone.” By the poet, the mother, who wants “to tell the girl he won’t be coming. / That it’s nothing personal. He died young.” By the admission, “Unless I look in the mirror / I can’t see him.” By the callousness of a friend who would ask if a mother is “over” her son’s death. By a mother’s very human reaction to such a question: “I want to ask my friend how her only daughter / is doing. And for one moment, I want her to tell me she’s / dead so I can ask my friend if she’s over it yet. / I really want to know.”

State of Grace: The Joshua Elegies is raw, brave, honest. It rips you apart as you read it–and leaves you grieving long after–because of the very vulnerable and wounded place from whence the poems arose. This is an incredibly compelling collection that does what lyric, confessional, narrative poetry does best: invites the reader into a human experience that is at once personal and shared, pairing vivid imagery and beautiful language with a story so moving that the reader is forever changed by the very act of having read it.

Want to see more from Alexis Rhone Fancher?

Buy State of Grace: The Joshua Elegies from Amazon

Four poems in Ragazine, including “When I turned fourteen, my mother’s sister took me to lunch and said:,” chosen by Edward Hirsch for inclusion in The Best American Poetry, 2016

Broad (“Dying Young” was first published in Broad)

Alexis Rhone Fancher’s Official Website / link to published works

![By Someone35 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://asitoughttobemagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/new_hampshire_in_autumn.jpg?w=700&h=525)