From HEMISPHERE

By Ellen Hagan:

RIVER. WOMAN.

I.

Downriver is always long

& always flailing, finding

where our lives begin,

intersect? You, your bones

the humped slope of nose

browned skin of home.

You, sand. You, ocean.

You, bending & me.

How many nights we sleep

alone, our bodies rising—

what it means to miss you.

What it means to expand.

What it means to be birthed.

What it means to be sacred.

What it means to go home.

Place of birth, birthing

ground. Ground that is sacred.

You that is sacred.

Bones that hold together. Bind.

Bound to you. My mother.

II.

Me

I am bound to you. My mother.

You stitch me from inside. Hollowed.

your split sheath of self, your letters

the slow cursive of your language,

can’t I hear your voice, always?

Her

Lock the doors. Latch the locks.

Shut the windows. Close the blinds.

Cover up. Clean your room. Do

the dishes. Wash the clothes. Behind

your ears, yourself. Clean the floor.

Scrub. Mop the remains every day

is one that you can use to erase all

the mistakes. Blemish free.

Shine the doorknobs, pine, every

crease of space. Cabinets. Don’t leave

food out. Food brings mice. Mice

bring disease. You will die. You could

die. Don’t die. Don’t ever die. You

stitch me from inside. I am bound

to you. Can’t you always hear

my voice?

LESSONS ON SPELLING

Bring the snakes in their skins, sly

& surrender. Simple bodies of grass

& clover, their slithering and sleuth-ness.

& the earth & the dusty fisherman

in from their boats, bobbing. Bring

piano, bring pain. That yellow skirt

pocked w/ fuchsia & the halter

of your mother’s pixie 60’s ways.

Let out the hems from your dresses,

the vertebrae in your back, body

forget skeleton—be loose, let it be dirty.

Get there. Call the black cat promenade,

lazy through the streets. Let your hair

down. Let it crawl, crowd the length

of your back. Bring soca & fiddle,

that record player your father bought

your mother in 1974. Bring all the days

from 1974 & on because time is a revolver.

A bag of limes on your back porch

squeezed & bitter & neon & orbiting

over you. Is your neighbor calling.

Is satsumas bursting on your tongue.

Bring your shiny shoes & arched soles

for the flapping pageant of second line

parade, the 100 parades from now until.

Autumnal. Hymns. Prayers.

Ways to say yes. Bring with you

your rope of hide, your many rings

of muscle & the washcloth

for your stomach, your feet

for the laying nape of your neck.

Bring danger & ways to hold your lips,

your lips, bring them too.

Spanning the whole of you.

You become.

WATER SIGN

Already a lullaby inside.

Your palms to belly, breath

on hip. You are changing,

beginning. Too. And you,

baby girl, or boy. Or two.

Are just gills. Still. Heart in

mouth. Red burst of newness.

Fins. Fish or fowl. Shrimp

are larger than you.

Still, you are breaking me

apart. Him too. Our hearts

and lungs, and gills. Bursting

You are stretching all,

all of us. Open.

Today’s poems are from Hemisphere, published by TriQuarterly Press/Northwestern University Press, copyright © 2015 by Ellen Hagan, and appear here today with permission from the poet.

Hemisphere: The poems in Hemisphere explore what it means to be a daughter and what it means to bear new life. Ellen Hagan investigates the world historical hemispheres of a family legacy from around the globe and moves down to the most intimate hemisphere of impending motherhood. Her poems reclaim the female body from the violence, both literal and literary, done to it over the years. Hagan acknowledges the changing body of a mother from the strains of birth from the growing body of a child, to the scars left most visibly by a C-section as well as the changes wrought by age and, too often, abuse. The existence of a hemisphere implies a part seeking a whole, and as a collection, Hemisphere is a coherent and cogent journey toward reclamation and wholeness. —TriQuarterly Press/Northwestern University Press

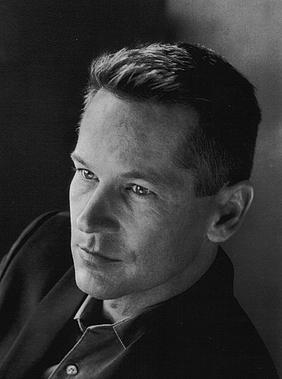

Ellen Hagan is a writer, performer, and educator. Her latest collection of poetry, Hemisphere, was released by Northwestern University Press in Spring 2015. Ellen’s poems and essays can be found in the pages of Creative Nonfiction, Underwired Magazine, She Walks in Beauty (edited by Caroline Kennedy), Huizache, Small Batch, and Southern Sin. Her first collection of poetry, Crowned, was published by Sawyer House Press in 2010. Ellen’s performance work has been showcased at The New York International Fringe and Los Angeles Women’s Theater Festival. She is the recipient of the 2013 NoMAA Creative Arts Grant and received grants from the Kentucky Foundation for Women and the Kentucky Governor’s School for the Arts. National arts residencies include The Hopscotch House and Louisiana Arts Works. Ellen recently joined the poetry faculty at West Virginia Wesleyan in their low-residency MFA program. She teaches Memoir, Poetry & Nature, and co-leads the Alice Hoffman Young Writer’s Retreat at Adelphi University. She is Poetry Chair of the DreamYard Project and a regular guest artist at the Kentucky Governor’s School for the Arts.

Editor’s Note: I fell in love with the poems in Ellen Hagan’s Hemisphere for their language: earthy, sensual, gritty. Unafraid of blood and birth, of mud and heat, of nature, of relationship, of what is real and lush and vivid, of what is primal and complex. I am reminded of the swamp, of the first creatures that dragged themselves forth from the murky depths, crawling forward, always, evolving for the sake of life. I am reminded, also, of witchcraft, of alchemy, of drawing down the moon. Of things my mother taught me, of that which has been handed down from woman to woman through the ages.

Today’s poems were meant to be, here, today. Because they are about the twin experience of birth—both as child and mother. Because much of this book is about the relationship between mother and daughter, the circle of life as only mother and daughter experience it: “where our lives begin, / intersect;” “what it means to miss you. / What it means to expand. / What it means to be birthed. / What it means to be sacred. / What it means to go home.”

In honor of Mother’s Day, and of the magic that grows from the rich soil of today’s poems, today’s feature is dedicated to my mother, the water sign, from your daughter, the water sign. “You that is sacred… I am bound to you. My mother.”

Want to see more from Ellen Hagan?

Ellen Hagan’s Official Website

Ellen Hagan’s Blog

Duende

Drunken Boat

Buy Hemisphere from Indie Bound