Tears

Skin once taut over muscle and bone

grows soft and softer still, as age moves on

and may bring sadness unknown before,

or a kind of thrill to mark the passage

on a map of being in this place, this age.

Adventures are remembered in crinkling folds.

Sitting or standing will require slower motion.

No matter the pain that is now no small matter.

An old drum at rest for a while needs the essential oil

of caring hands, each touch and each beat deepening

into warm inviting sounds, smelling of vanilla rain.

Pitter patter, falling softly. Softly enfolded in loved arms.

Hush and listen, safe and dear one, ever close to heart,

where ear is at the center, just as art is in the earth,

and ripples continue beyond the edge of the pond.

About the Author: Geraldine Cannon is a poet, scholar, and editor, also working as a Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Maine at Fort Kent, under her married name–Becker. She has been published in various journals and anthologies. She published Glad Wilderness (Plain View Press, 2008).. She has been helping others publish, and had stopped sending her own material out, but she was encouraged to do so again, and most recently has a new poem in the Winter issue, Gate of Dawn (Monroe House Press, 2024).

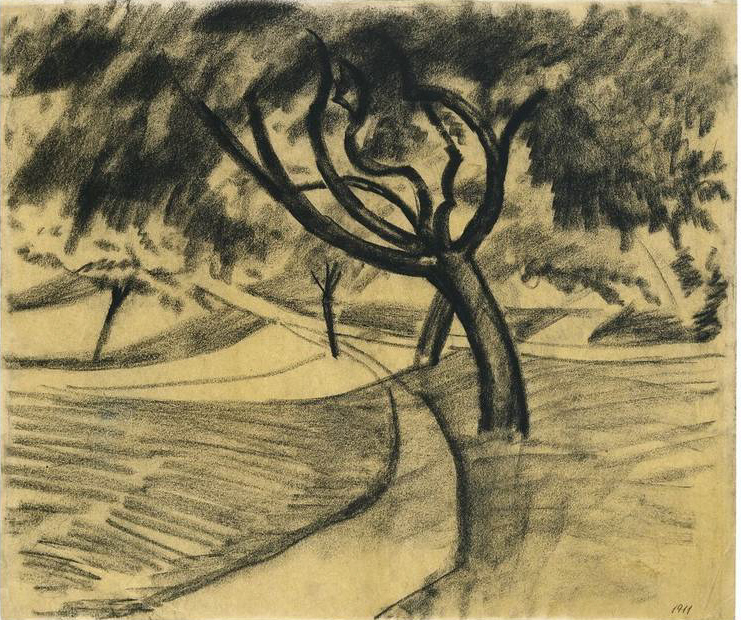

Image Credit: Jan Ciągliński “Rain – impressions from the train” Public domain image courtesy of Artvee