Hugs to Chance

by Angela Townsend

…

It is there in my own script. “Hugs to Chance!” If there is anything we should entrust to the lottery, it is not hugs.

But fifteen givers call their creatures Chance, so I ballpoint my embraces. “Hugs to Chance!” This is what you do when you are the Development Director for a cat sanctuary. You buy blue pens in bulk so you can add personal notes to every tax receipt. You remember the names of donors’ pets. You send the animals hugs. You send hugs to Chances.

Hugs to Roxy are one thing. Hugs to Vercingetorix require careful cursive. The personal touch will be lost if I misspell the cat’s name. I practice on sticky notes before committing caresses to letterhead. Hugs to Vercingetorix, the warrior of nineteen ginger pounds. Hugs to Vercingetorix, whose name was Pumpkin until he was diagnosed with cancer.

When I tuck hugs between the signature line and the benediction that no goods or services were exchanged, givers write back.

Joan accuses me. “You know I can’t resist.” If I send Joan a photograph, even if I assure her that the kitten is fine, she will send fifty dollars. The kitten called Dumpling may sit fat in love’s stew. Joan still sees the wet and ragged. She boils over. She signs for the delivery of my hugs and sends a thank-you note with another fifty dollars. I wonder if Joan switches to no-name detergent when she can’t resist kittens. I wonder if she stops long enough to hug Roxy for me.

Gert’s ink bleeds. Vercingetorix is no more. “I don’t know when I am going to be okay again.” Gert does not say “if,” but “when.” She has been here before. Her Boots once became Genghis, and Tigger became Valkyrie. Their urns bear both names. Gert, in paisley pull-on pants, rode beside them into war. Gert gave insulin at twelve-hour increments and purchased Cornish hens for cats on hunger strikes. She rides with a ghost army to teach Sunday School and stack cans at the food bank. She does not know when she will adopt again. “If” would be the wrong word. She bought a stuffed animal the size of a nineteen-pound cat. She holds it in her arms so she can fall asleep.

Anthony knows it’s risky to name a cat “Chance.” His daughter once brought home a stray she called “Lucky,” and Anthony made her change it. Why tempt the stars, you know? Anthony’s letters have so many rhetorical questions, he has to type them out. His maintenance man found a cat in the boiler room and fed him Chef Boyardee. Anthony is not making this up. The maintenance man worried he would get in trouble. The cat’s eyes were all pupils, blind as Ray Charles. He’d been in the dark too long. That’s what happens. Anthony caught the maintenance man. The cat was eating toddler pasta from a spoon. The maintenance man cried, saying, “we give him a chance, we give him a chance.” So, “Chance” is a finger in fate’s eye. Do I understand? He can’t give Chance hugs, because Chance will bite his face. He’ll translate “hugs” into Chance.

When you are the Development Director, stories tattoo you. I try to tell donors that they ride in my front pocket, and some days I can’t stand up straight for the weight. I am not sending hugs so they will give us more money. I am sending hugs because they are inked into my skin. I want to invite all fifteen Chance people to a holy convocation. I want them to compare notes on how the Chances came. I want to collect all the naming ceremonies in a single volume. I want the story with the big arms.

I don’t tell them my story. When you are the Development Director, it is not about you. I start sentences with the word “you,” because the donor needs to know that they are the hero. They may not know when they will be okay again, but they know that they are the reason Dumpling will live. Love answers to “when,” not “if.”

About the Author: Angela Townsend is the Development Director at Tabby’s Place: a Cat Sanctuary. She graduated from Princeton Seminary and Vassar College. Her work appears or is forthcoming in Arts & Letters, Chautauqua, CutBank, Lake Effect, New World Writing Quarterly, Paris Lit Up, The Penn Review, Pleiades, The Razor, and Terrain.org, among others. Angie has lived with Type 1 diabetes for 33 years, laughs with her poet mother every morning, and loves life affectionately.

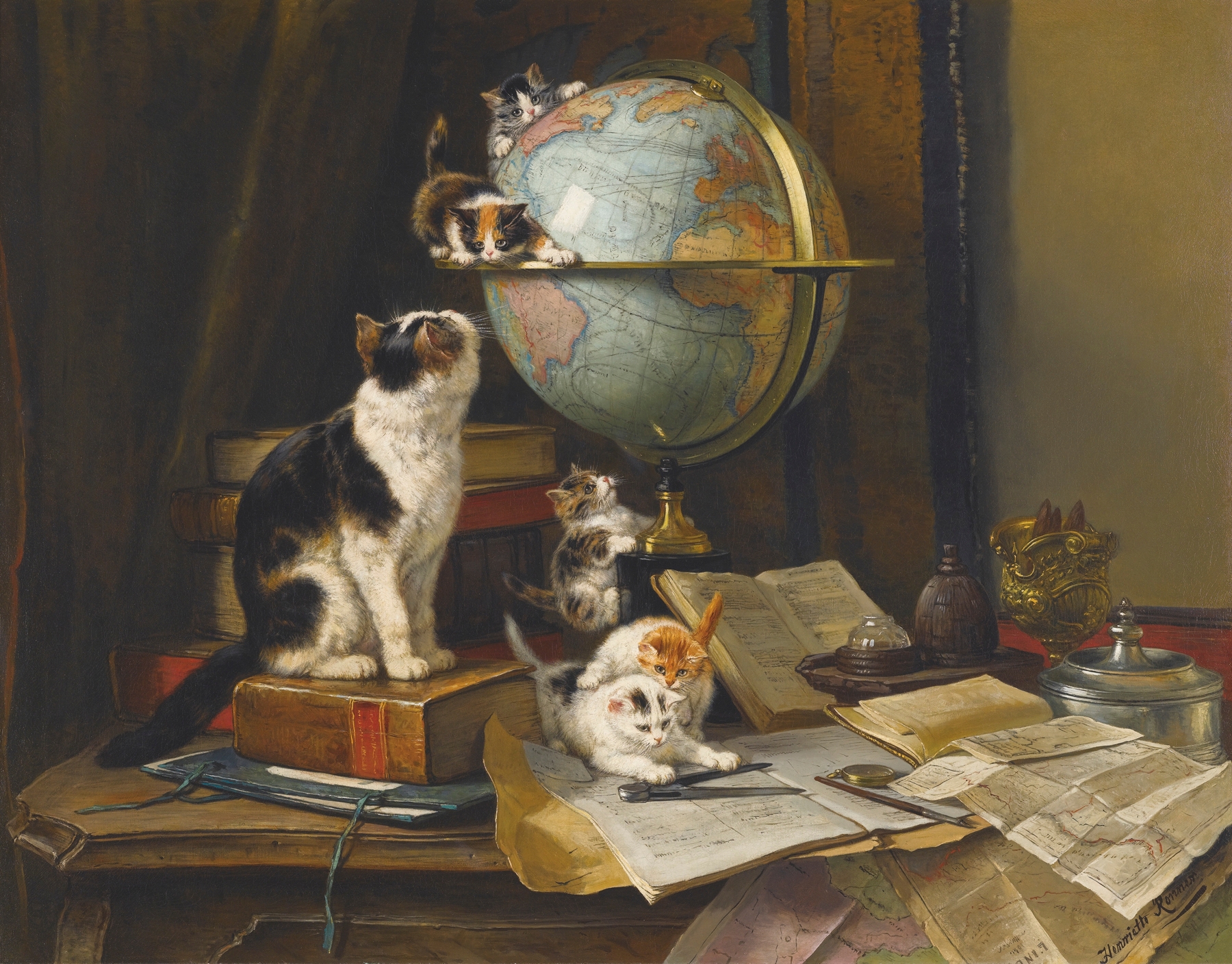

Image Credit: Henriëtte Ronner-Knip “The Globetrotters” Public domain image courtesy of Artvee