Wardenclyffe

The present is theirs. The future, for which I really worked, is mine.

-Nicola Tesla

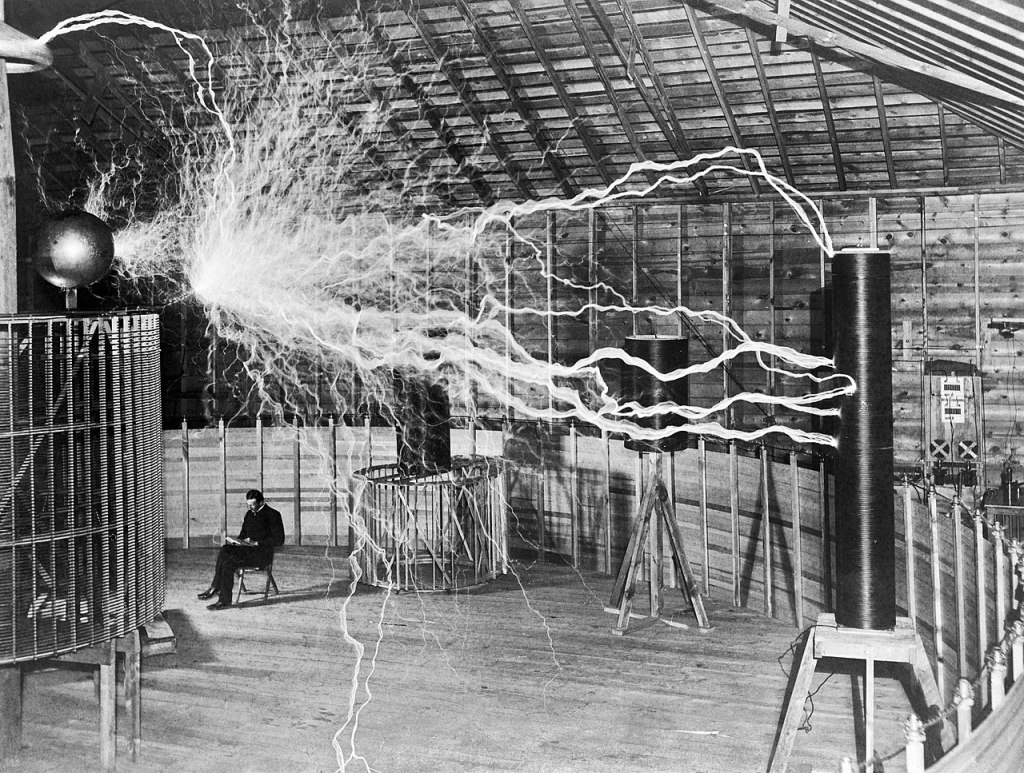

Is what I imagined tangible—

this motor, powered by fireflies,

streamer arc threads of phosphorescent light

discharging from the center coil.

I go from idea to reality,

a star among the stars.

I do not think there is any thrill

like the inventor seeing a creation come to success,

the exhilarating sense of the future.

Sometimes we feel so lonely.

Someday we will know who we really are.

If my current can travel distances,

my work is immortal—

resurrecting my vision, broadcasting to Mars.

Thought is electrical energy.

Why can’t we photograph it?

The primary circuits of us all,

high-speed alternators—

many colors, myriad frequencies.

Sometimes we feel so lonely.

Someday we will know who we really are.

My tower dream ran out of funds—

demolished to scrap,

the property sold to the highest bidder.

I live on credit at the Waldorf,

along with spark-excited ghosts.

My only friends are pigeons in Bryant Park—

My favorite is a female.

As long as she lives,

There is light in my life.

Sometimes we feel so lonely.

Someday we will know who we really are.

About the Author: Susan Cossette lives and writes in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The Author of Peggy Sue Messed Up, she is a recipient of the University of Connecticut’s Wallace Stevens Poetry Prize. A two-time Pushcart Prize nominee, her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Rust and Moth, The New York Quarterly, ONE ART, As it Ought to Be, Anti-Heroin Chic, The Amethyst Review, Crow & Cross Keys, Loch Raven Review, and in the anthologies Fast Fallen Women (Woodhall Press) and Tuesdays at Curley’s (Yuganta Press).

Image Credit: “Tesla sits with his “magnifying transmitter” in Colorado Springs in 1899″ Image courtesy of Wikipedia. CC BY 4.0