Cope

By J.D. Isip

– for Jeff Albers

Who by aspersions throw a stone

– George Herbert, “Charms and Knots”

At th’ head of others, hit their own.

“Professor Isip,” my student is a little angry, holding up her laptop to me, a wiki for David Foster Wallace, the bandana photo, “You didn’t tell us he killed himself?”

It’s not the first time a student has confronted me about this. I’ve assigned Wallace’s 2005 Kenyon graduation speech, “This Is Water,” for well over a decade. Generally, maybe because these are freshmen who need something to believe in, maybe because it’s just that good, they fall in love. And, as they do, they dive all the way in—want to know everything about him.

“Does that make a difference?” I ask, still curious myself.

She is shocked, “Yes!” She thinks about what to say, “I’m not saying he’s bad for killing himself. I know… I have a friend” she wrote about this friend in her first paper. There’s a lot of them who have a high school friend who committed suicide. A lot of them want to write about it.

When Infinite Jest came out, I didn’t know who David Foster Wallace was or that he was important. I was at a military base in Turkey trying not to be gay. When I went back to get my MA, it was 2008. I was in Dr. Bonca’s class getting ready to talk about postmodernism when he sat down at the front table and cried. He’d met him. Maybe they were friends, I can’t remember. I just know he meant that much to Bonca.

Wallace opens the speech with a story about two fish swimming and an older fish asks them, “How’s the water?” They wait for the older fish to pass and ask one another, “What the hell is water?”

“But if you’re worried that I plan to present myself here as the wise older fish explaining what water is to you younger fish, please don’t be,” though this is exactly what Wallace does for the next twenty or so minutes of the speech. I let my students listen to the speech in class. Recently, I’ve picked up on the eeriness of listening to the dead.

A large part of graduate school, for me, was bitching about how postmodernists got it all wrong. What the fuck did all of that deconstruction have to offer any of us after September 11th? Sometimes students ask me about 9-11 like it’s some far off time recorded in a textbook, certainly nothing the living know about firsthand, “How did you get over it?”

These days they mean September 11th, but they also mean what should have been their formative years spent locked inside, spent behind a mask, spent stuck. I think of President Bush saying we needed to go to Walt Disney World to beat the terrorists, so we went. We got back to living. We pantomimed what we remembered about living.

Almost five years later, Wallace gives this speech at Kenyon. It “goes viral,” or whatever the equivalent of that was in 2005. In academia, the postmodernists were aware of the crumbling support for their ways and their work. You don’t need a young scholar to tell you that you’re old news. Whatever this new thing was didn’t have a name. Maybe post-postmodernism. The New Sincerity? Some have settled on Metamodernism. But I liked “The New Sentimental.”

“How do you get over it?” my students want to know about moving past all these lost years.

The morning the towers fell, I was just getting to work at Disneyland. We weren’t going to open, of course, but there were all of these families basically trapped in the hotels. They couldn’t leave, and they couldn’t go to the parks. All their excited kids just wanted to get on rides, they had no idea the world was ending.

The foods folks made these elaborate baskets of Mickey-shaped cookies, muffins, croissants, really heavy fruit. Each of us would join a few characters, I was with Snow White and Winnie the Pooh, and knock on the doors of the guests. The kids were all screams and hugs, the parents kept looking back at the television screens. Snow White would kneel down to every kid, even the taller but terrified twelve-year-olds, and say, “I know what it’s like to be afraid” and then she’d tell them her fairy tale, a condensed version for some… an elaborate version for others.

When we got back to the golf cart, two baskets empty, Snow White put her head in her hands and cried. Pooh took his head off and massaged her shoulders.

“I don’t know how you get over it,” I tell my students, “I honestly don’t know if you ever do get over it. I’m just an English professor. All I know to do, all that’s ever worked for me is to write it down. Tell your story.”

Some of them try to bury the lead, nearly a page of description before anything happens. Others want to tell me statistics about all the dead, from the plague and from the suicides and from being in the wrong place at the wrong time. One of my creative writing students says, “Professor Isip, do you think this is too hokey?” He’s one of the best in the class, grandson, or great-grandson of Larry McMurtry. “I don’t want to come off as too sentimental.”

Wallace was known for these meandering ideas that would try to distance the reader from the moment. As he’s being repulsed at a cruise ship buffet or a porn convention autograph booth, he drops in some random facts to draw the gaze away from his visceral reactions. If you were looking for the signs, you might have picked up on a guy refusing to own what he was feeling, or even who he was.

“Did you know he was an abuser?” another student asks me, again the accusing tone.

This, of course, has made me reconsider using the speech. I reason I’d have to cut out a whole lot of my readings if I had to cut every fucked-up writer; I don’t know a writer or an academic or a person in general who isn’t a little fucked up. I suppose that is what the kids would call “cope,” and maybe it is.

“Yes. I can assign you something different if you like,” I offer. Nobody has ever taken me up on this. None of them bring it up in their papers. I don’t think it’s because it doesn’t matter. I think it’s because, like me in Turkey, they’ve got other shit on their minds. And, again, they tend to like what he’s saying in the speech. They don’t write about his suicide either.

He keeps driving home the point that we have a choice about how we see the world. We can deconstruct the life of a dead man, psychoanalyze his relationships, come to the conclusion that everything and everyone is fucked-up or, worse, meaningless. You can give in to the nihilism or depression. You can drink or get high, screw your brains out. Hang yourself. Or…

When she finally composed herself, Snow White asked Pooh to hand her the makeup bag. She looked at herself in her compact, “How many more stops do we have?”

I didn’t want to say it, “That was only the first floor. We aren’t even finished with this hotel. I just wanted to get you out here for a break.”

She laughed, that way between sincerity and madness, “Well, let’s go back in” dropping the lipstick back into the bag, “I’d rather be Snow White than me right now.”

The New Sentimental was, if I remember correctly, something about a return to belief. That if all these decades of postmodernity had revealed something “more real” than the real, then maybe there was something beyond that, like Plato’s Realm of Forms. Like heaven. Like something to believe in.

She’ll be Snow White because you need her to be Snow White. He’ll be the David Foster Wallace of the 2005 speech because you need that version of him. Because you have a choice of how you see this world.

And maybe that’s cope. And maybe that’s okay.

About the Author: J.D. Isip’s full-length poetry collections include Kissing the Wound (Moon Tide Press, 2023) and Pocketing Feathers (Sadie Girl Press, 2015). His third collection, tentatively titled I Wasn’t Finished, will be released by Moon Tide Press in early 2025. J.D. lives in Texas with his dogs, Ivy and Bucky.

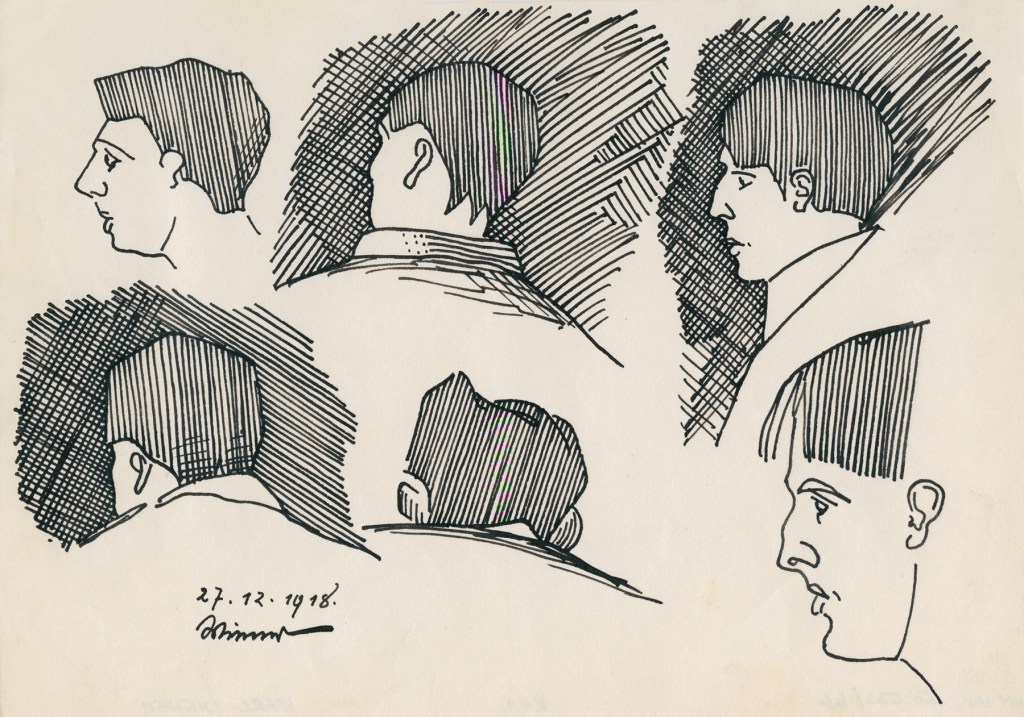

Image Credit: Karl Wiener Ohne Titel (Köpfe) (1918) Public domain image courtesy of Artvee