It’s 2023, and We Still Need to Read Sally Carrighar

By Sue Blaustein

The late author Sally Carrighar’s work is out of print. Between 1944 and 1975, Carrighar (1898-1985) published one novel, eight works of “nature writing” and an autobiography (Home to the Wilderness). Two of her books One Day at Beetle Rock and One Day at Teton Marsh were made into Disney features, making those titles very well-known.

I must’ve read one or more of her books when I was in grade or middle school. As an adult, I found them while browsing used bookstores. They looked familiar, and I bought and read them again. By that time, I was a poet with a day job – better prepared to appreciate how exact, humble, and brilliant a writer; and how meticulous an observer she was.

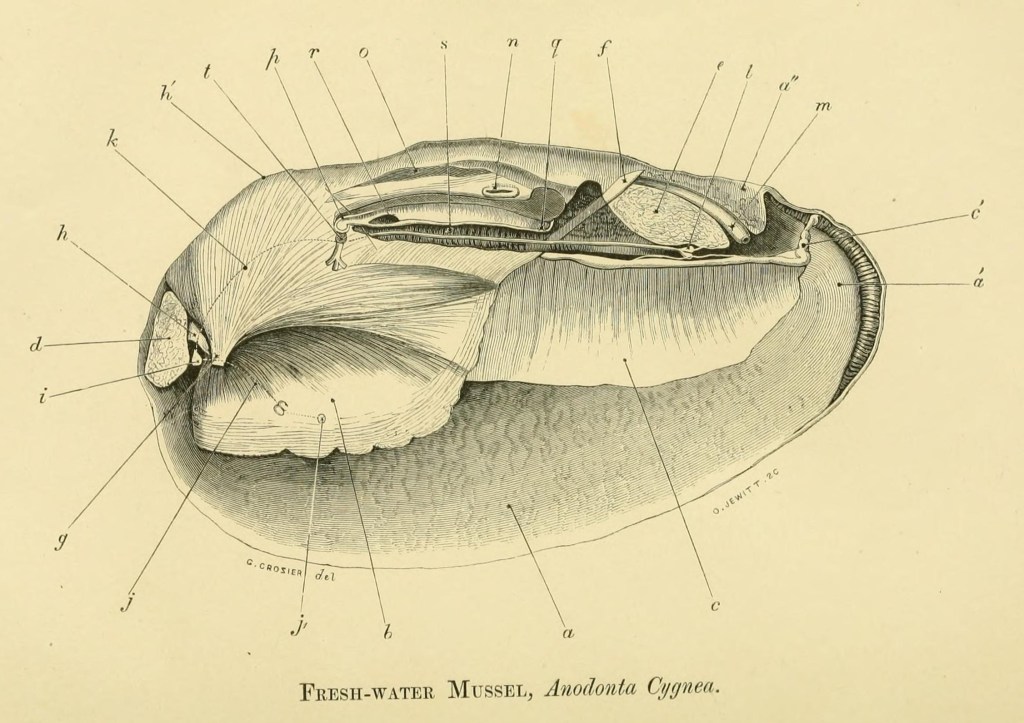

If you’ve never read her work, you don’t know yet, how in a few paragraphs – say about the reproductive habits of a freshwater mollusk – she could expand and reshape the way you see non-human creatures, yourself, and the world we inhabit together.

The swan mussel was not nearly as complex a creature as man, but even she had her satisfactions, and a simple nervous system with which to experience them.

Every creature – swan mussels included – has vital and specific needs. If those needs are satisfied, we live. Of course, the word “satisfy” carries layers of other meanings for humans. Most likely few if any apply to our mussel. Carrighar’s deft use of the word satisfactions doesn’t load mollusks up with human emotions and yet…it opens the door to kinship.

How does the mussel breathe and eat? Carrighar explains how it pulls water into one tube and expels it through the other, thus receiving oxygen for the gills and minute plants and animals for nourishment.

No doubt she enjoyed some draughts of this living broth more than others; on windy days when the pond was stirred, the greater amount of oxygen may have felt rather invigorating. These were not very stimulating events, but the mussel was not equipped for excitement.

Enjoyed? Invigorating? Though these words come close to attributing human perception to a mollusk, they make a valid point more vivid. For any creature, no moment is the same as the one before, or ones to come. Experiencing and responding to change is what nervous systems are for. The language opens a portal, a way to imagine what it’s like to be something else. A way to care.

The paragraphs quoted are from her 1965 book Wild Heritage – a popular introduction to what was then referred to as the “new science” of ethology. Wild Heritage was a synthesis of all she’d learned writing her first five books. Rigorous study of animal behavior – that included structured observation and experiment – was coming into its own as a discipline. Behaviors were understood to be as key to evolution by natural selection as physical changes. Hope for gaining insight into human behavior – particularly problems of aggression and war – fueled popular interest in the subject.

How did Sally Carrighar become a lay scholar of animal life and a “nature writer”? She wasn’t trained as a scientist like Rachel Carson. She came of age after the era when devoted “amateurs” of natural history (like Charles Darwin) could make their marks.

Her 1973 autobiography Home to the Wilderness explains. Mental illness – her mother’s – and the attendant trauma inflicted on Carrighar, determined the unusual and courageous trajectory of her career.

Carrighar’s birth was complicated – intensely painful and terrifying for her mother. Forceps deformed her face. Her outwardly normal, socially prominent mother was not only unable to bond with her; but could scarcely tolerate her daughter’s presence. When Carrighar was six, in a moment of rage, her mother tried to strangle her to death.

The book is too complex for a tidy recap. Eventually, she got care, insight, and treatment from a psychoanalyst and decided on writing as a career. She’d lived through profound trauma in family life, then worked for business publications and in Hollywood among volatile, ambitious, and unpredictable people.

During periods when she was nearly penniless and suicidal, her exceptional powers of observation, and affection for animals literally saved her, as she drew comfort from a flock of birds congregated at her apartment windows. The stability she saw in their lives and relationships led to the epiphany that concludes Home to the Wilderness! She scrapped her unsatisfying attempts at fiction to learn and write about animals.

Her works are grounded in the extensive study she launched upon making this decision. She developed relationships with scientists in the field and acquainted herself with the literature. Eighteen pages of footnotes in Wild Heritage attest to the breadth and depth of her study.

The lifelong need to cope with the pathology of her family life endowed her with exceptional watchfulness and sensitivity. Once she was settled in for her solitary stays at Beetle Rock and Teton Marsh, this quality made her an apt student of the rules of engagement that guide sharing of resources between and within species.

She learned from seemingly benign experiences like distributing nuts to ground squirrels, and from a potentially deadly encounter and standoff with a bear that approached her cabin. Carrighar was too continuously attuned and responsive to elevate or debase herself in relation to other animals. She matter-of-factly studied her own fear, then anger, as the bear upended her life for days on end. Her narratives are credible, free of judgment or over-stretched analogies.

There’s an astounding level of intimacy in her descriptions. A moose feeds: He closed the slits of his muffle and probed in the ooze. The end of his nose, of his muffle, was almost as soft as the ooze itself. It scooped in the feathery muck, touched a firmness and the object suddenly crumbled – a decaying branch.

The nature and role of instinct and the varied capacities of non-human animals were also much studied and contested in the early days of ethology, as they still are. Carrighar observed animals so completely in relationship to each other and their environment that her treatment of instinct has a nearly supernatural certainty and clarity.

In One Day at Teton Marsh, the day chronicled is at or near the autumnal equinox. A storm blows in and topples a tree that wrecks the beaver dam that created and maintained the marsh habitat. Snow falls for the first time. This is the change that leeches, snails, mosquitoes, and frogs; ospreys, mergansers, and herons; otters, moose, mink, hares, and beavers respond to, each in their way.

We feel a Merganser mother’s conflicting urges to keep tending her nearly capable young or migrate on time. We feel how irritation might arise in a particular creature, in particular circumstances:

Dabbling ducks were a trial, adding now to the strain of her days. The Merganser lived in a higher key than they. She was more intense, with her energy focused more finely, except when the dabblers distracted it. She herself often caught a whole day’s food in a single dive. The others foraging, leaf by leaf, bug by bug, must go on, noisy and obvious…

Carrighar included human-animal interactions, as the Merganser’s arrival in breeding grounds was briefly delayed by interest in a human’s daily ritual of feeding ducks at her winter home. She hints at the possibility of individuality – a human whose demeanor creates trust, and a Merganser more receptive to this attention than others…

She shows a swan whose erratic behavior and declining health are due to ingestion of lead shot. Her mate is forced to choose between leaving her to guide their young or remaining at her side. Her narratives show how creatures must and do make “choices” when circumstances introduce conflict.

Sally Carrighar’s last book – the autobiography Home to the Wilderness – was published just a few years after the first Earth Day formally opened the era of environmental consciousness. Fifty plus years of research in all disciplines have elapsed, so clearly some aspects of her work are dated. I thought about this when re-reading Icebound Summer, an incredible account that weaves together the lives of creatures in the farthest north.

Polar ice – its colors, movements, and influence on the lives of living beings (human and non-human alike) – is described in spectacular detail. Icebound Summer was published in 1953 and I can only imagine what’s been wrought since by climate change. Yet this “dated” account conveys such a deep understanding of relationships in nature that it holds its value.

In her work, Carrighar repeatedly contrasted the law-governed character of animal life with the lives we live as humans: But we also create, deliberately it sometimes appears, a degree of irregularity that nature would never tolerate. We take risks that result in sudden and shocking tragedies; we endure situations that cause the unstable to turn to violence; international tensions that could be talked away are allowed to deteriorate into wars.

I think about all the grossly maladaptive behaviors – mass shootings, domestic abuse, suicide, ecocide and endless war – that are on the rise and banishing our sense of well-being. How did this come to be?

In “The Silenced Bell” – the chapter in Wild Heritage about mating and reproduction – Carrighar describes the way instinctive, intricate behavior patterns and exquisite timing support successful reproduction and survival. Things become more complicated in the lives of primates.

She explores the evolution of mating behavior in the animals like us, whose brains have evolved to the point where we can decide: No one knows just when it happened, but obviously at some stage, the developing mind of the primate glimpsed the momentous idea that he need not wait to be moved by instinct. He could take initiative, reach for the things that delighted him.

That’s our dilemma, as humans. We can make decisions that don’t necessarily assure our survival or health. We can compromise the survival of our and other species, since we’re no longer restrained by instinctive brakes that stop us from taking more than enough. We’ve evolved the means to override restrictions that protect other species from self-destruction.

Carrighar’s love for animals animates her brilliant prose. Yet she didn’t moralize about human dysfunction or romanticize animals. She had too deep an understanding of evolution for that.

In Home to the Wilderness, she stated: Basically, wild behavior is biological. The fixed traditions have been acquired through the long millions of years while the present species have been evolving; and these traditions have become established in animal genes because they are the ways that work. This is the kind of behavior that has insured survival, just as physical features like camouflage or……have helped to insure [sic]the survival of species that have them. She points out: That behavior conforms to our definition of “moral”.

Carrighar had preserved her own hard-won sanity by living close to non-human animals, learning. She didn’t use them as metaphors or command her readers to empathy. Her goal – pursued with humility but tremendous conviction – was simple. She felt that wilderness life furnished lessons humans need for a return to stability and health, and built a career sharing what she knew of these ways. She didn’t formulate or advocate policy, but her warning was compelling:

…we are apparently bent on destroying the wilderness, which could be the most tragic development in the history of the human race. For if the wilderness is reduced much further, we shall have no clues to nature’s moral sanity – none except our own now-devastated instinctual guidance. Can we find that again, shall we have enough sensitivity?

Her question haunts me. We’re living through cycles of nauseating, apocalyptic news, and silly distractions. Our social life feels more chaotic all the time – graceless and dangerous. I think it is. It’s tempting to think of Carrighar’s era as a relatively idyllic “before-time”. But wars (including but far from limited to World War II, Korea and Vietnam) were as constant during her life and career as they are in our time. The extraction and exploitation of every natural and human resource that drove 20th century postwar prosperity was in full force. Now the bill is coming due and it’s scary.

How can it help to read books about the lives of various animals, books written from fifty to nearly eighty years ago? For one thing, we have to get up and make our way each morning without giving in to despair and disgust, and this prose is soothing. Her observations train our eyes, ground us, and boost whatever sensitivity we already possess.

There are herons, Canada geese and mallards in the park where I walk dogs. Fishing birds and dabblers – and I remember the nervous Merganser. Damsel flies alight on the sidewalk, shadows cross and they move on, and I remember how the animals in Teton Marsh sensed weather changes. On a breezy day, I wonder if any pond mollusks are feeling that extra measure of oxygen.

In Icebound Summer a polar bear and herd of walruses engage in a deadly combat. As the enraged walruses rush one end of the ice floe, it shifts, and they slide into the sea in a bellowing mass. Reading that at the end of a stressful day, I chuckle at the image like a child with a picture book. I calm down.

We need to understand and appreciate interrelatedness and interdependence, and no one described it better and more accurately than Sally Carrighar. We need beautiful writing, and her prose is unsurpassed. We need to develop sensitivity and we need to calm down; and for that, a stack of her books is indispensable.

About the Author: Sue Blaustein is the author of “In the Field, Autobiography of an Inspector”. Her information can be found at www.sueblaustein.com. Recently she contributed a poem to a “The Subtle Forces” podcast episode and was interviewed on the “Blue Collar Gospel Hour”. A retiree, she blogs for Milwaukee’s Ex Fabula, serves as an interviewer/writer for the “My Life My Story” program at the Zablocki VA Medical Center, and chases insects at the Milwaukee Urban Ecology Center.

Image Credit: Image originally from Forms of Animal Life;. Oxford, Clarendon press,1870. Courtesy of the Biodiversity Heritage Library